We have long understood that measuring an economy’s development and performance in quantitative (financial) terms, such as Gross Domestic Product, causes harmful distortions and places the wrong priorities first. Limits to Growth issued a dire environmental warning in 1972 about the dangers of unchecked population increase and resource shortages on a finite earth. Recent research reveals that we are currently extremely close to seeing the collapse situation of “business as usual” that the authors of the study warned of, even though some of the forecasts made were postponed by the incredible resilience of the planetary system. Limits to Growth was updated 30 years later with a focus on:

“Sustainability does not mean zero growth. Rather, a sustainable society would be interested in qualitative development, not physical expansion. It would use material growth as a considered tool, not a perpetual mandate. […] it would begin to discriminate among kinds of growth and purposes for growth. It would ask what the growth is for, and who would benefit, and what it would cost, and how long it would last, and whether the growth could be accommodated by the sources and sinks of the earth.”- Meadows, Meadows & Randers (2005: 22)

What we need is a more sophisticated understanding of how early (juvenile) stages of biological systems favor quantitative growth whereas later (mature) stages favor qualitative growth (transformation) rather than quantitative increase.

“It seems that our key challenge is how to shift from an economic system based on the notion of unlimited growth to one that is both ecologically sustainable and socially just. ‘No growth’ is not the answer. Growth is a central characteristic of all life; a society, or economy, that does not grow will die sooner or later. Growth in nature, however, is not linear and unlimited. While certain parts of organisms, or ecosystems, grow, others decline, releasing and recycling their components which become resources for new growth.” — Fritjof Capra and Hazel Henderson (2013: 4)

We cannot comprehend the nature of complex systems like organisms, ecosystems, communities, and economies if we explain them in exclusively quantitative terms, claim Capra and Henderson in their joint article on qualitative growth. The necessity to map rather than quantify characteristics arises from the fact that “qualities develop from activities and patterns of interactions” (ibid: 7). There are many similarities between how ecologists and economists interpret the ideas of growth and development. Ecologists and biologists understand how to distinguish between the qualitative and quantitative components of both growth and development, in contrast to economists who frequently use a purely quantitative approach.

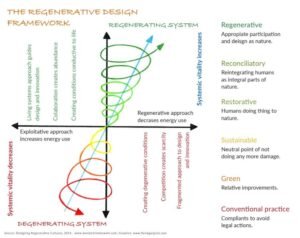

In ecosystems, a “succession” of slower growth and maturity stages replaces the “pioneer ecosystems'” rapid expansion phase. Living systems transition from quantitative to qualitative growth as they get older. The logistic curve, as opposed to the exponential curve, governs the growth patterns of life. Cancer cells, which ultimately kill their host, are one type of living system with aberrant quantitative growth. Quantitative growth that is unchecked is harmful to economies and biological systems. By contrast, qualitative growth “may be sustained if it incorporates a dynamic equilibrium between expansion, decline, and recycling, and if it also contains development in regards to learning and maturing”

A deeper socio-ecological comprehension of their impact can help to clarify the difference between good growth and bad growth. Good growth is defined as the development of more effective production processes and services that fully internalize costs associated with renewable energies, zero emissions, ongoing resource recycling, and ecosystem restoration. Bad growth externalizes the social and ecological costs associated with the degradation of the Earth’s eco-social systems. According to Capra and Henderson, switching from quantitative to qualitative growth might help nations transition from ecological unpredictability to ecological sustainability as well as from unemployment, destitution, and waste to the creation of worthwhile and respectable jobs.